Worship, Hoard, Possess: The Creed of Disoriented Societies

We don’t follow faith. We follow fandom.

This piece was originally published in French in magazine singulier, a print magazine launched on 26 March, 2025, edited by éditeur singulier under the direction of Victor Napias and C.A.M. magazine singulier is a collision: where fashion meets literature, where aesthetics and language intertwine. This essay explores the cultural mutation of faith in an era of disillusionment—how obsession, collection, and consumption have become the new sacred rituals.

"The need to escape the tyranny of time and dissolve into ecstasy responds in him [Baudelaire] to this taste for the infinite and this cult of beauty, which he never ceased to associate, even in his final spiritual and moral torments."

— Albert Béguin, L'Âme romantique et le rêve, 1939

The dissolution of the self into a cult, any cult, is an ancient need. Etymologically and historically, fanaticism is tied to excess, to extreme fervour. Voltaire condemned it1, seeing it as a fever of the mind, a social gangrene. What was once dismissed as fringe delirium now fuels the engine of modern life.

In a world in crisis, where traditional structures crumble and the future feels more uncertain than ever, fanaticism hasn’t disappeared. It has mutated.

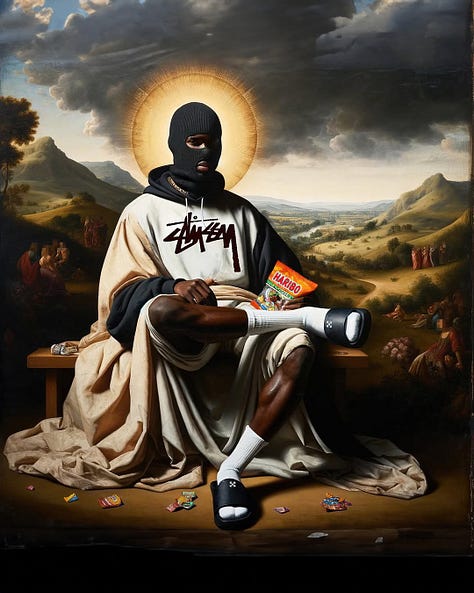

Today, it’s no longer just the Idea that mobilizes crowds, but fandom. A cult that swapped gods for brands, scripture for content drops, and dogma for franchise lore. Far from being mere entertainment, this fanatic culture has become a belief system, an escape, a way to structure both individual and collective identities. Has fanaticism become the last refuge of an unmoored era?

Obsession as a Value System

English has a word for this fervour: fandom. A mental territory, a belonging, a kingdom where passion isn’t questioned. Sometimes, passion metastasizes into obsession. Stan culture—named after Eminem’s song Stan—depicts these extreme fans, oscillating between devotion and harassment. Japan has long been a testing ground for this dynamic. The Otaku culture, coined in 1983 in Manga Burikko, originally described obsessive pop culture fans—socially awkward, confined to their own world. This perception took a dramatic turn with the 'Otaku Killer', whose horrific crimes linked the term to pathological isolation and deviant obsession. The dark irony? In Japanese, Otaku literally means "home." A culture of retreat, of fanaticism as shelter from an alienating world.

Once dismissed as fringe behaviour, these patterns have become the norm. According to a recent study2, the majority of individuals define themselves as fans of something, finding in it both social validation and identity. In an age marked by loneliness and the erosion of collective markers, fandom offers refuge, a second skin, a means of existing.

The internet has accelerated this phenomenon. No longer passive, it’s a creative war machine. Fans don’t just consume their obsession; they generate content around it. They are no longer spectators but architects, constantly feeding a shared universe. Online, fan fiction isn’t just teenage escapism—it rewrites myths, reshaping narratives through an obsessive lens. Meanwhile, Charli XCX isn’t just playing the inaccessible pop diva—she’s orchestrating a cult where every fan is both priest and co-creator of her maximalist universe.

This otaku fanaticism—an obsession bound to the walls of one's own world—is supercharged by algorithm-fed dopamine loops, wiring society intravenously to digital solitude. Beneath the frantic need for belonging lies an undercurrent of terror—the terror of the void. Fandom culture feeds off institutional collapse, engineered loneliness, and the slow erosion of human bonds. It’s not just a refuge—it’s a survival instinct.

The Church of Capital

Fanaticism and cults are inseparable. And cults have never needed deities to exist.

"The cult of ancestors, of heroes, of the dead; the cult of the city, the family, the nation, the tribe; the cult of the land, of friendship, of art, of strength, of honor, of reason; the cult of money, of idols."

— Jean-Richard Bloch, Destin du siècle, 1931

The words cult and culture share the same root. Since the 16th century, cult has referred to religious homage paid to a deity or saint. Meanwhile, culture evolved from cultivated land to the act of honouring—of worshipping—something or someone.

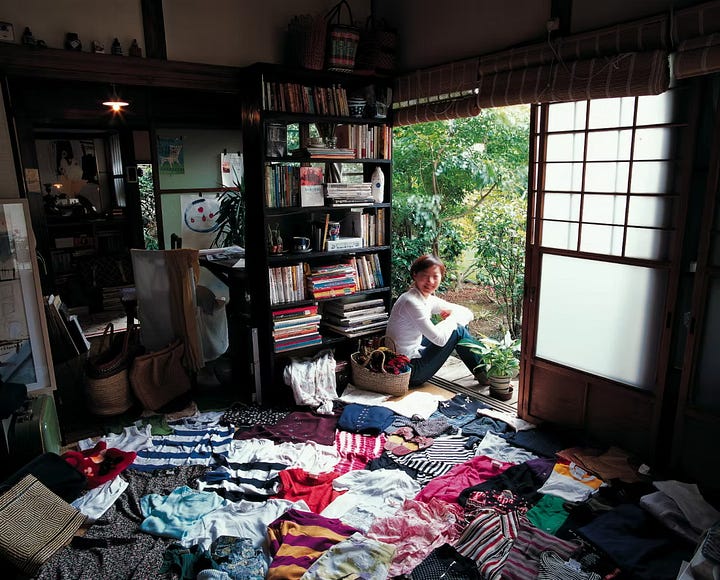

Today, capitalism itself is the supreme cult, and brands are its cultural temples. In its most extreme—and yet entirely mainstream—forms, this veneration of the object becomes an overdose: compulsive accumulation, hoarding, clinical syllogomania. Not just a craving—a compulsion. Not just a whim—a doctrine of excess. Japan's Tsundoku—the accumulation of unread books—is its most refined expression: to own an object is to embody it.

Accumulation becomes a spiritual act. Fashion collectors aren’t mere consumers; they are archivists of contemporary relics. Photographer Kyoichi Tsuzuki captured this obsession in Happy Victims: Japanese devotees sacrificing their entire existence at the altar of Hermès, Vivienne Westwood, Chanel, Margiela. Flats transformed into chapels, possessions turned into totems. Product fetishism as a declaration of self: You are what you buy.

But this cult culture doesn’t exist without its own language3. On social media, we follow digital spiritual leaders, preach in comment sections, convert others by sharing our obsessions. Whether in fashion, music, or literature, fandom has become a secular faith structure, where consumption is no longer a mundane act but a profession of faith.

To consume or to worship—either way, it numbs the void. If your cult is niche, you become a cultural guru, a trendsetter. If your cult is mainstream, you dissolve into the masses, lulled by the syrupy softness of mass entertainment. Either way, your existence anchors itself to a belief—whether exclusive or shared.

A Faith for the Faithless

Fanaticism, once pathologized, has seeped into the operating system of our time. In a world where traditional markers of meaning dissolve, fandom has become a sanctuary, a framework, an identity matrix. More than mere passion, it’s a way to structure reality, to make sense of it.

Collecting is an act of faith, consumption a ritual, fandom a form of communion. Beneath the layers of accumulation, adoration, and collective creation, one question lingers: Is fandom an escape or a symptom? A space of freedom, or yet another form of submission?

Perhaps, in this contemporary chaos, believing in something—even a brand, even an idol—is better than believing in nothing at all.

In Case of Doubt is a media for the age of great uncertainty, acting as foresight researcher & strategist Elodie Marteau’s editorial arm. Reach out to further inspire your brand’s future, ensure its cultural relevance, and future-proof its strategy.

Voltaire, Dictionnaire philosophique (Philosophical Dictionary), 1764

Amanda Montell, Cultish: The Language of Fanatism, 2021

Thank you for this essay and especially for introducing the Happy Victims art project. We confuse purchasing and consumption with community and belonging in today's world.